Other Sources of Lost Happiness

I began by wondering if the West, and especially the U.S. (bigger and better at everything), had managed to develop social and cultural systems not well fitted to the life satisfaction and happiness that arise from well-founded life choices and life courses. The U.S. excels at this quasi-dystopian process as it gives the appearance of a nation indifferent to the quotidian suffering arising from poverty, ill health, economic and racial inequality and their consequently disparate opportunity, and the more dramatic suffering inflicted by our national security policies on other countries. By way of contrast, other developed nations do not consider taxes a demon’s levy and are unwilling to see their countrymen go, for example, without heath care merely because they are poor. Americans are a callous and parochial people except on select occasions.

While it should be obvious how many of the prevailing U.S. practices are not good for the citizenry, there are other sources of misfit between people and society that are not so obvious. Human nature requires a base level of security and stability to maintain most people’s sense of safety and well-being. We need life to be reasonably predictable with stress not absent but manageable and motivating. But rapid change has become normal and imposes the cultural expectation that it is the hapless citizen’s duty to adapt just as it has been since the Luddites registered their well-justified objections in the early 19thcentury to the wreck of their way of life by industrial imperatives, which it turned out would be enforced at the point of a gun by mill owners and the English government. (American government has responded similarly to outbreaks of labor unrest particularly around the turn of the 20th century.) In his book The Shipwrecked Mind, Mark Lilla attributes the nostalgia of reactionaries to the impact of destabilizing modernist processes, which have broader effects than that as he also noted: “To live a modern life anywhere in the world today, subject to perpetual social and technological change, is to experience the psychological equivalent of permanent revolution. Marx was only too right to remark how all that is solid melts into air and all that is holy is profaned…he [the reactionary] blames modernity tout court, whose nature is to perpetually modernize itself. Anxiety in the face of this process is now a universal experience…” (p. xiv)

The signs and symptoms of this anxiety are legion. The election of an ethically reprehensible but clever manipulator of such anxieties in the U.S. stands out along with those European politicians who have traveled much the same route with varying success. Changes in the nature of work and compensation have produced objectively threatening circumstances for many and scapegoating of immigrants, undocumented and documented, has been drafted into false association with those circumstances to intensify the feeling of real threat by the addition of trumped-up versions. Refugees, most of whom our own policies have played major parts in displacing, are made to serve the same purpose even while relatively few are admitted to the country. Add in black people, LGBT people, Muslims, and whoever can be made to serve as object of bias du jour and anxiety over change, and the threat it may or may not present, can be made useful to opportunists. It is unfortunate that legitimate anxiety, which deserves attention on its own terms, is turned to political purposes that aggravate rather than mitigate the perceived threats.

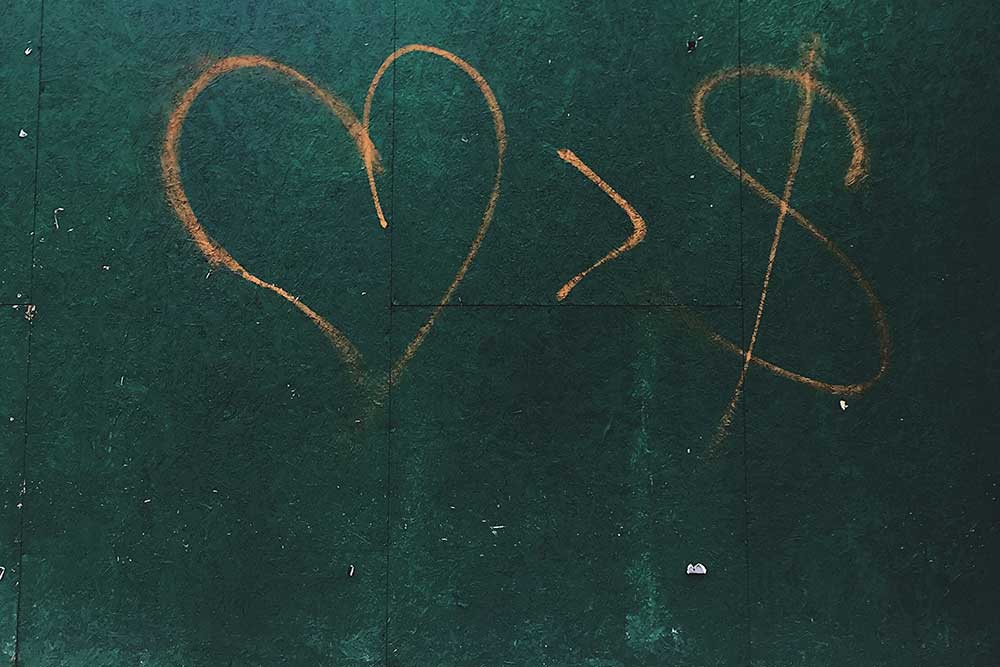

The problem of change is at least twofold: its pace and nature and the division between those who see it as beneficial and those who are threatened by it. The underlying and too little addressed issue with it is this: Change for what purposes, change toward what ends, change for whose benefit? One needn’t deny that some changes are useful while seeing that many are superficial and trivial and serve little more than economic ends. But all are to a degree disruptive, some are destructive, and all are accompanied by unintended, negative side consequences. It was Thoreau I believe who noticed that people built things to own which eventually came to own them. Is change like that? It has its own momentum and its own imperatives and with the prevailing caveat emptor, laissez-faire U.S. value system, operated under the aegis of its economic system and its ruling class servitors, it just goes on and on to no one knows where. And the casualties are all those whose simple need and desire for reasonable security and well-founded happiness are thwarted by changes beyond their control and very often their understanding.

This is the 5th part of an 8 part essay.

Photo by Jon Tyson on Unsplash