A few days later, Douthat’s Times colleague David Brooks weighed in:

For many people, the gun is a way to protect against crime. But it is also an identity marker. It stands for freedom, self-reliance and the ability to control your own destiny. Gun rights are about living in a country where families are tough enough and responsible enough to stand up for themselves in a dangerous world. (“Guns and the Soul of America,” 10-6-17)

The dark side of individualism and the sense of being under threat in a dangerous world: these speak to the reality of too much and too quick change as the experience of half or more of our population, made worse by the weakness of social supports and community solidarity to undergird the bright side of individualism; and the propensity of certain politicians and cable personalities to exaggerate and manipulate the sense of threat for their own purposes.

I’m not ready to give up on what seems appropriate despair but if there’s an antidote, I want to imagine what it would look like. If we chose to seek happiness and to address the factors that have stood in the way, one aspect of that transformation might consist of returning to the ancient question that asks what a person lives for and looking to see if there’s anything in reflecting upon that that might help, even aside from answering it, for reflection has value in itself.

As far as I know all of the major religions, many ancient philosophical schools, and most contemporary “spiritual but not religious” belief systems conceive a state of enlightened union with an Absolute, in one form or another, as their ultimate experience and abiding awareness. As that perception moves toward the practical level of expression through active engagement with the world it turns into a quest for insight into reality and compassionate living. I take it that such experience and such outcomes are real and of the greatest value. I also take it that even without awareness of these ideas, humans’ nature is to need and desire the solidarity and mutual care that they represent. When there is too little mutuality in daily living or in the institutions that theoretically were designed to serve essential human needs, we are unhappy, often deeply and sometimes pathologically. Some manifest that in addiction to drugs, alcohol, work, money, and so forth. Some kill themselves and some kill others. Recall some of the variables focused on in the World Happiness Report and Bhutan’s Gross National Happiness study: caring, generosity, good governance, community vitality, honesty, ecological health. And relate those to the present state of things. I have thought for many years that the central dysfunctions in the U.S. were economic inequality (and its wide-ranging ripple effects), climate change and our blasé response, and domestic violence and foreign militarism, to which I now add pervasive truthlessness and corrupted, unresponsive government. If these are the problems, I imagine them to be, and if they contribute in manifold ways to national unhappiness, they are suggestive of ways toward more satisfying and meaningful lives. Not simply in reaching the goals, say, of better governance or community vitality but in the shared effort toward elucidating and realizing them. In this, people define and live toward the moral basis for happier society and begin to heal alienation from self and others.

The way in to confronting any of these American curses, these failures of our national life, begins at the basic level of just facing their reality, acknowledging their existence and perniciousness, their deadly weight upon our souls. When a man takes suitcases loaded with guns and ammunition to a hotel, ascends to his room, and shoots hundreds of people below who are unknown to him and certainly no threat as at Las Vegas…when adolescents take guns to their school and proceed to kill classmates and teachers as at Columbine (and too many others to count) …when…when…There is more to these stories than individuals gone mad. While it is plausible that more Americans are mentally disturbed per capita than in otherwise comparable countries, it is unlikely that there are proportionately as many more as there are episodes of mass killing here compared to others. In other words, an angry, deranged American is far more likely to take that out violently on others than if he were a citizen of another society. And that screams out for understanding: What’s wrong in this society? Facing reality accepts that something is terribly wrong here and seeks to identify it. I could imagine after Las Vegas or Columbine the nation calling a moratorium on all nonessential work or other activity for a period while people gathered in small groups to define what’s present and what’s missing that feed this monster.

Similarly with our history of racism and native American genocide, our actions in Viet Nam and now the Middle East, our failing democracy and failed social compact, our acceptance of daily lies. All of these, the fact of them, the denial of them, the accommodation to the suffering they impose, all together foster American unhappiness, which is another word for a lack of well-being and moral-social flourishing within communities and a society where care is a preeminent value. In the words of the World Happiness Report 2017, it is “a multi-faceted social crisis” that the nation faces, or rather that it is confronted with but refuses to face.

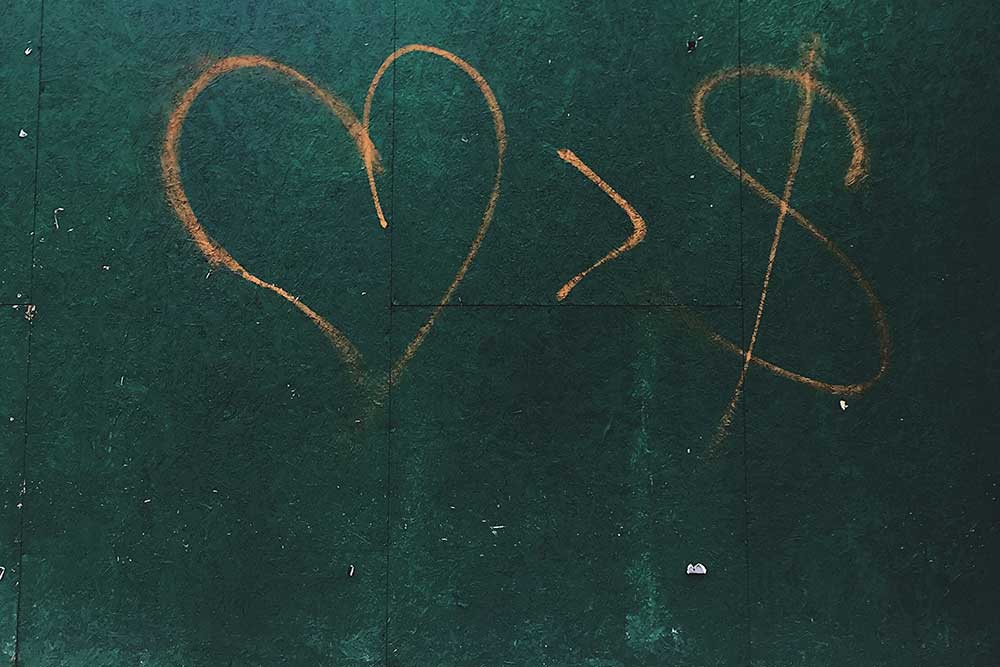

The place of guns in American society, and acceptance of their uses (over 30,000 dead annually, a third of these by homicide), may be as close to a perfect stand-in as we have for all that is wrong. As Douthat and Brooks noted above, they represent identity, safety, and self-reliance and often the dark and isolated expressions of these. They are also dangerous tools of violence and whatever positive value they have is surely far outweighed by their harms. Over recent years while American levels of happiness have declined significantly there has been a corresponding rise in the belief that protection of gun rights is as important as limiting access to them, and this despite the flow of blood onto the ground. It is also the case that as mass shootings occur states under Republican control follow up with even looser restrictions on gun purchases. Presumably, this is a manly way of demonstrating a lack of queasiness in the presence of hemorrhage. Or a thumb in the eye to those who think that more guns might mean more deaths (which they do) and to demonstrate their resolve to defy fact and sentiment, to be unmoved from the defense of their gun rights, to assert the right to guns over the right to life. One can understand the innocent sounding role of gun ownership in identity formation, but such understanding is incomplete without seeing the continuity of the present gun fetish with centuries of American violence.

There is a natural impulse to seek fundamental causative factors, whether for illness, dysfunction, or other concerning events. What starts a ball rolling which produces an array of consequences? Guns we might say are symptomatic of our propensity toward violence and social fragmentation, but where do the violence and fragmentation come from? I propose a cultural disregard for life, even though that too sounds symptomatic, but of what I can’t discern; it may just stand on its own, mixed into the national foundation. It goes as far back in this country’s history as I can trace, and it is something I can easily imagine as self-reinforcing once in motion. It takes obvious forms that we’ve noted, including slavery, genocide, ecocide, and war. More subtly it shows as the continued absence of universal health care (the unspoken text behind this obviously: if you can’t afford care you’ll just have to suffer and perhaps die), the highest incarceration rate on Earth, the positive correlation between white gun ownership and racism, and failure to come to terms with extreme biodiversity loss and climate change.

Another symptom picture arises in response to an event like the Las Vegas killing spree, one which unconsciously conveys triviality while reinforcing denial of the spree’s cultural meaning and arousing patriotism at the same time—a week after the killing a college football game was played in Las Vegas and it “honored the victims” (Honor? Why not memorialize? Where’s the honor in being randomly killed?) by wheeling out an American flag of a size to cover the entire playing field (it took 250 volunteers to unfurl the thing); a football official was “proud” to “pay tribute and honor those that were killed or injured”; it incorporated a video tribute to the victims, red ribbons were attached to the players’ helmets; “first class” in all respects said the official; first responders to the calamity were also honored as the game has been designated “Heroes’ Night.” “It’s very unfortunate circumstances but it is very appropriate that the Big Flag will be there in Las Vegas to honor the victims,” said the official. The continuity between this pageantry and that following 9/11, which has still not abated as fulsome prelude at sporting events, is obvious and seems to suggest that in both cases innocent Americans were victims, even though at Las Vegas they were victims of our own tolerance for violence and at 9/11 of many years of violent and hegemonic foreign policies. A tragic expression of long-standing life denial is turned into an assemblage dedicated to the arousal of emotion, which is then turned outward; no self-examination but plenty of self-glorification and self-pity.

The occurrence of the Las Vegas killing comes while I have been writing and I consider it confirmatory of my thesis. The observations of many of those who have responded publicly have noticed that in countries with strongly restrictive gun laws the presumption is that the damned things are dangerous, and a person has to demonstrate his competency and trustworthiness to own one. Oppositely, in the U.S. the right of just about anybody to own one is considered inviolate and the real job is to restrict the government’s ability to control them. What comes first in this conviction is obvious.

Why are more and more of us, those who do not fetishize guns and know that a life-affirming country would restrict them, throwing up our hands in despair and recognizing that this is just who we are and that while we cannot tolerate a single life lost to “terrorism” we adjust well to the knowledge that the nation lives within a revolving door out of which a certain number will regularly be violently expelled at mass killing events after having been randomly, or sometimes purposefully, shot, usually by an angry and freedom-loving white guy with his guns? I believe that we now realize that it’s something like this: if you were considering buying an old house that was not in prime condition, it would make a telling difference if you knew it was basically sound and needed only paint and a few repairs. But if it was clear that the frame had been ravaged by termites and the foundation tilted by shifting ground and the roof leaked, we’d know better than to buy it; remodeling to make it a happy place to live in would require vast expense and time and patient investigation of the major weaknesses and what their repair would entail. Who can believe that that reckoning will ever happen in the American home?

If, as mentioned earlier, our highest potential is expressed in union, with God or Nature or fellow humans, then it may be that the greatest deficit humans can face is lack of union, separation, isolation. The path to multi-faceted happiness, toward the flourishing of individuals-within-communities of solidarity and care is as good as any I see toward remediation of our “multi-faceted social crisis.” And in saying that, despair at the prospect of any but a few following that path reappears. Combine centuries of national pathology with present nihilistic floundering, and the manipulation of both by a ruling class to maintain power and wealth, and with a people who are inured to truthlessness to the point of choosing a man like Trump to solve their unhappiness (another symptom of its implacability), and the trajectory can only be downward. We are who we have always been and getting worse. Or so it seems at this moment.

###

This is the concludes an 8 part essay.

Photo by Jon Tyson on Unsplash